Nangohns Massey, a member of the Little Traverse Bay Band of Odawa Indians, was killed in her home in November of 2020. She was 21 years-old and has a son, who is now three. Her family has been waiting nearly a year for justice.

“She was such an amazing person, honestly,” says her cousin, Mia Pamp, a member of the Little River Band of Ottawa Indians. “She had an amazing outlook on life. She always looked for the best in people. She was such a friendly person, like a friendly spirit.”

Her story is all too familiar for Native American communities across the nation.

“So many people can relate to that in the indigenous community because so many people have had family members, sisters, friends and cousins, aunts, grandmothers, mothers- everyone has somebody,” says Pamp.

In some counties, Native American women are murdered at rates ten times higher than the national average, according to a . The murder rate of Native and Alaskan/Pacific Islander women is three times higher than non-Hispanic White women. It’s been called an epidemic.

Amid the saga of the Gabby Petito case, people have been calling out for the same attention and resources to be used in solving Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Two-Spirit cases.

The hashtag “#findgabbypetito” has been used to raise awareness about the numerous missing people of color across the U.S.

“I feel strongly for Gabby Petito’s family and I hope that they are okay, and my condolences will always be with them,” says Pamp. “But it’s just so unfortunate that there’s not that same energy for the 710 missing [indigenous] in Wyoming, the same state where Gabby Petito went missing in.”

Wyoming’s Missing and Murdered Indigenous People’s Task Force says that 710 people Indigenous people were reported missing in the state over the past decade. Over half of them were female. They make up three percent of the state’s total population. Native American females are murdered at a rate 6.4 percent higher than white females.

The issue isn’t restricted to the West. It happens in Michigan. But everywhere, the statistics and cases are grossly underreported.

Holly T. Bird is an attorney. She is also serving as an Associate Judge for the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi Indians. She has also served as a Chief Judge for the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians. She says there is a disparity in the investigation, enforcement and prosecution of cases related to indigenous people.

The National Crime Information Center reports, in 2016, 5,712 missing American Indian and Alaska Native women and girls. However, the U.S. Department of Justice’s federal missing persons database, , only logged 116 cases.

“They stopped counting,” Bird says. “There is no accurate database in law enforcement currently to account for all of the missing relatives that we have.”

Bird herself knows 20 people who have gone missing or were murdered. And as a judge, it once took three days to seat a jury for a domestic violence case because everybody had experience with domestic violence and couldn’t be neutral. Four out of five Native American women will experience violence in their lifetime.

“That’s what happens when you have family dysfunction that’s brought on my oppression,” Bird says. “When you have people that have been in boarding schools, beaten and sexually abused. I know that a lot of these issues, people don’t understand. People don’t realize we only just got into resources. You can’t get rid of 500 years of oppression and dysfunction in 20.”

She says that racial bias and a lack of resources is to blame for this epidemic.

“When we see something like the situation with Gabby Petito get blown up in the media and get put out there and a rush of law enforcement agencies from multiple states to try to find her we just go, why didn’t that happen for my sister, my auntie or my niece,” Bird says.

She says we need resources to help and support tribal law enforcement and prosecution agencies, but also outlying communities. Education on racial bias and accountability are also part of solving the epidemic.

“Nangohns Massey, who was related to people here in our area, was murdered,” she says. “We only recently got a charge of murder that was fitting for that fact pattern.”

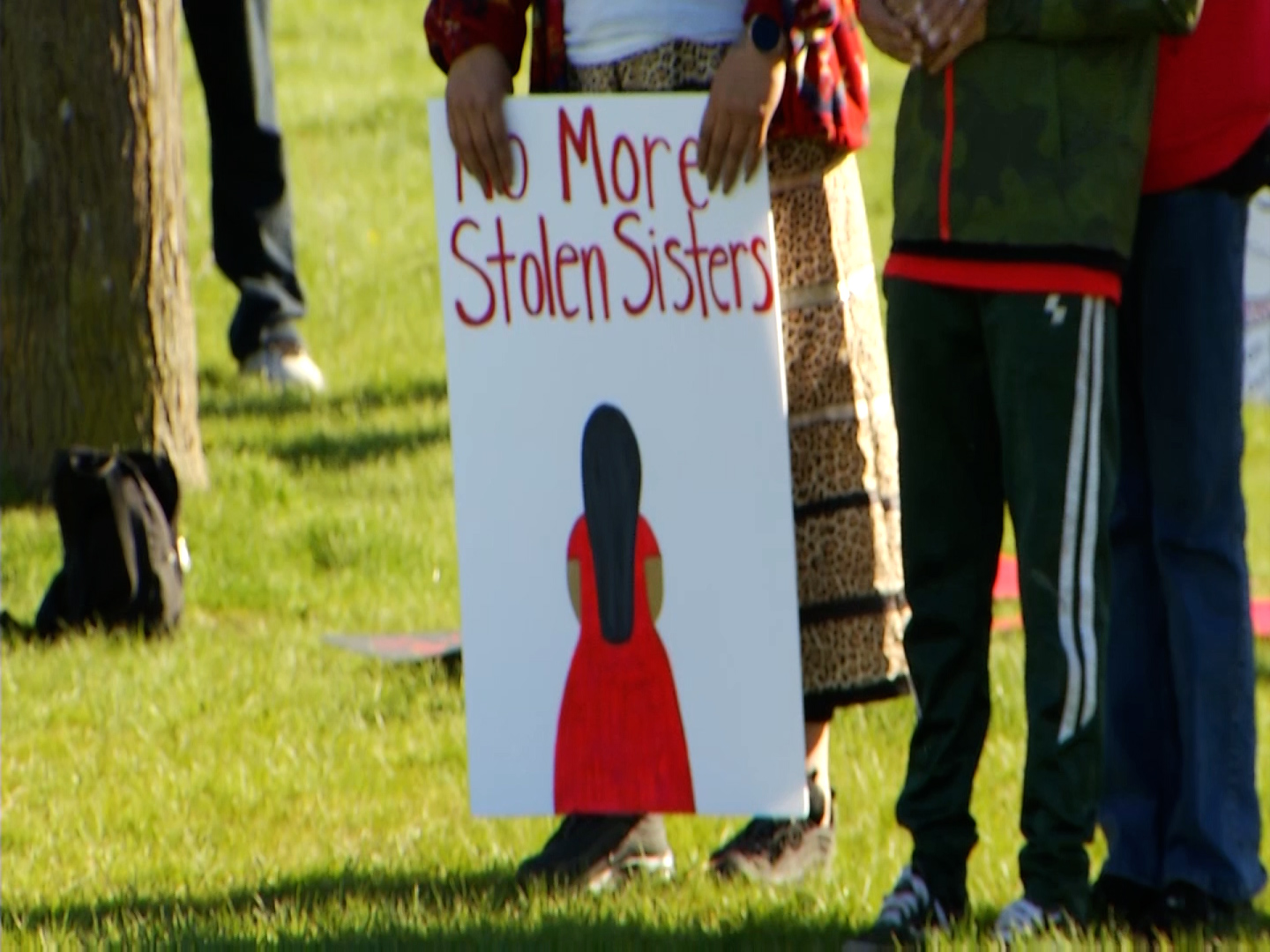

Several rallies in Detroit and Grand Rapids have been held for Massey and to raise awareness about MMIW cases.

“We’ve been throwing rallies and it’s been primarily her community of people that have showed up,” says Pamp. “We’ve been able to gain somewhat of a presence, but unfortunately she never really did anything like Gabby Petito did…she didn’t really gain much social media presence.”

© 2023 - 910 Media Group